一、

I.

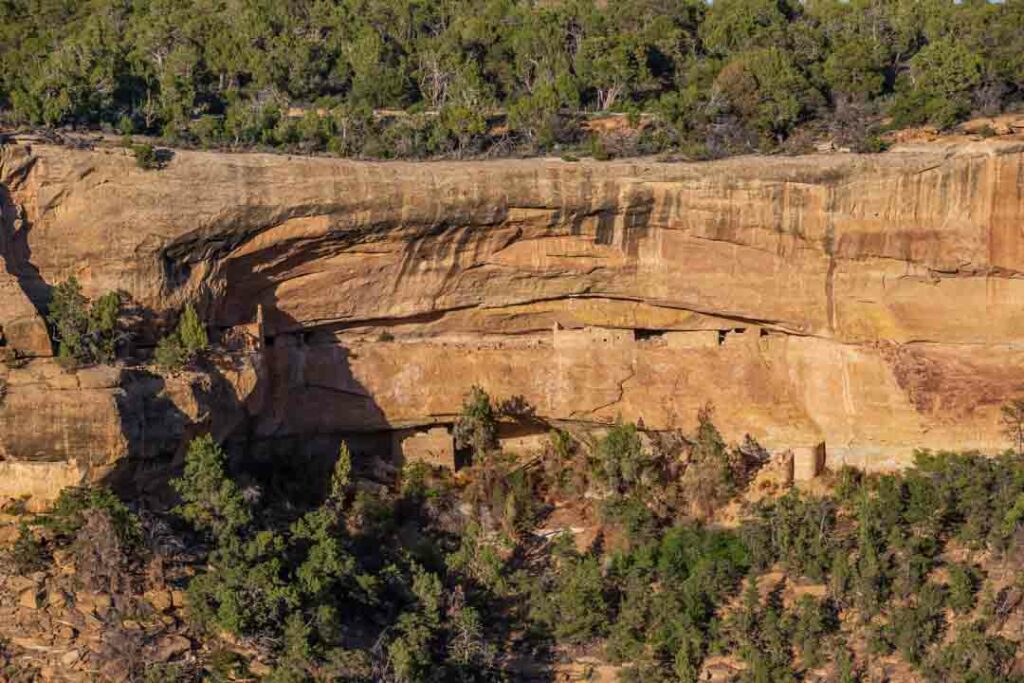

当理查德·韦瑟里尔(Richard Wetherill)和他的姐夫梅森在 1888 年的十二月来到台地边缘时,这片峡谷里的一切都变了。透过漫天飘扬的雪花,这两位牛仔依稀分辨出峡谷对面悬崖上如同雕刻出的层层叠叠的房屋。在随后的十几天里,他们找到了一条通往这个被他们称为“悬崖宫”的山间小路。他们花了几个小时走遍了悬崖宫的数百个房间。根据梅森的回忆,他们捡起几件他们感兴趣的物品,其中包括了一把仍然有柄的石斧。

When Richard Wetherill and his brother-in-law Mason arrived at the edge of the mesa in December 1888, everything in this canyon changed. Through the swirling snowflakes, the two cowboys faintly discerned a series of intricately carved houses on the cliff opposite the canyon. Over the next few weeks, they found a trail leading to this place they would later call the “Cliff Palace.” They spent several hours exploring the hundreds of rooms within the Cliff Palace. According to Mason’s recollection, they picked up several items of interest, including a stone axe that still had its handle.

他们很可能并不是最先发现这处令人震惊的遗迹的人。在他们记录下这一切之前,除了世代居住在附近的犹他人(Ute),许多外来的捕猎者、探矿者和传教士都曾拜访过这片地区。但相比这些短暂停留的外来者,生活在本地的理查德有充足的时间仔细探索这里,并能在这片复杂的山地中为后来者充当向导。

They were likely not the first to discover this astonishing archaeological site. Before they documented everything, many outsiders, such as hunters, prospectors, and missionaries, had visited the area, apart from the indigenous Ute people who had been living nearby for generations. However, unlike these transient visitors, Richard, being a local resident, had ample time to thoroughly explore the region, and eventually served as a guide for later explorers in this intricate mountainous terrain.

悬崖之上,壮丽遗迹存在的消息在短时间内轰动了全世界。1891 年,前来探险与挖掘的人中多了一个来自瑞典的学者诺登斯基德(Nordenskiold)。熟悉地质学和化学的他教会了当地人科学的挖掘手段,带走了遗址中大批最有价值的文物,并为世人留下了数张珍贵遗址照片。他将自己在梅萨维德等地的经历写成了《梅萨维德的悬崖居民》一书。因为地处偏远而交通不便,诺登斯基德的照片和描述让更多的人第一次见识到了这处奇迹,并促进了美国政府立法保护的决心。

Above the cliffs, news of the magnificent ruins spread rapidly worldwide. In 1891, another explorer and excavator, a scholar from Sweden named Nordenskiold arrived. Proficient in geology and chemistry, he taught the locals scientific excavation techniques, took away numerous valuable artifacts from the site, and left behind several precious photos of the ruins. He chronicled his experiences in places like Mesa Verde in a book titled “The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde”. Due to its remote location and difficult accessibility, Nordenskiold’s photos and descriptions introduced many people for the first time to this wonder. This strengthened the determination to protect it through legislation by the United States government.

一百余年过去,今天的悬崖宫依旧保持了当年照片里的风貌。

Over a century has passed, yet today’s Cliff Palace still retains the appearance captured in those old photos.

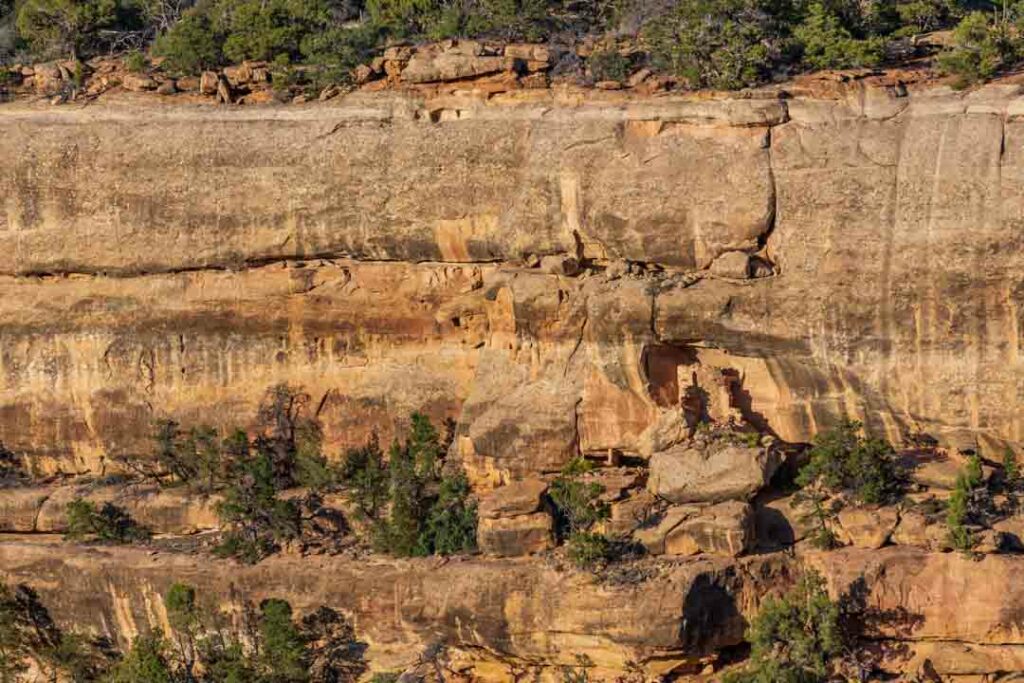

当然,梅萨维德的重要性不仅在于悬崖宫。悬崖宫只是整个国家公园中六百多座悬崖住宅里最大的一座。这些隐蔽在崖壁凹槽的高耸住宅大多建造于梅萨维德鼎盛的十二中叶至十三世纪(也被称为古普韦布洛文明三期)。

Certainly, the significance of Mesa Verde extends beyond just the Cliff Palace. The Cliff Palace is merely the largest among over 600 cliff dwellings within the entire national park. These towering residences hidden in alcoves along the cliff walls were mostly constructed during Mesa Verde’s heyday from the 12th to the 13th century, a period also known as the Ancestral Puebloan civilization’s “Classic” or “Pueblo III” era.

由于南方其他古普韦布洛人定居点因为广泛的干旱而崩溃,来自四面八方的稠密人口带来了精细的陶器和耕种技术,聚集到了这个不算发达的悬崖谷地。这片深山中的荒凉地带摇身一变,成为了古普韦布洛文明的中心。

Due to widespread droughts, many other settlements of the Ancestral Puebloans to the south collapsed. As a result, a dense population from various regions congregated in this less arid cliff valley, bringing with them sophisticated pottery and farming techniques. This once remote and barren area in the mountains transformed into the center of the Ancestral Puebloan civilization, flourishing with life and culture.

相比于更早的普韦布洛遗迹,这一时期的悬崖建筑有着更复杂的结构以及标志性的塔楼。人们将开凿的石块进行繁琐的切割,使之成为整齐的长方体。石砖被白色或红色的石膏仔细而紧密地贴合在一起,构筑出房屋的多重墙壁。这使得村落中比原先更高大的建筑有了更长的使用寿命。至今,梅萨维德已发现了超过一百座塔楼。这些塔楼可能被用作防御堡垒或避难所,也可能作为瞭望台以供天文观测,或是用于保护部族获取的自然资源。在后期,一些塔楼地下还修筑了通往普韦布洛人圆形祭祀建筑——基瓦(Kiva)的暗道,这可能意味着塔楼与祭祀和神性的关联。

Compared to earlier Puebloan ruins, the cliff constructions of this period feature more complex structures and iconic towers. People meticulously cut the quarried stones to form neat rectangular blocks. These stone bricks were carefully and closely fitted together with white or red plaster to create multiple walls, providing the larger buildings in the village with extended lifespans. To date, Mesa Verde has revealed over a hundred towers. These towers served various purposes, such as defensive fortifications or shelters, observatories for astronomical observations, or protection of the tribe’s acquired natural resources. In later periods, some towers were connected underground to circular Puebloan ceremonial buildings called “Kivas,” which may indicate a connection between the towers and rituals or spirituality.

如今,这些高塔使得梅萨维德的建筑看起来更加错落有致,展现出了更早期普韦布洛遗址无法体现的视觉美感。

Today, these tall towers give Mesa Verde’s architecture a more staggered and visually appealing appearance, showcasing a sense of aesthetics that was not evident in earlier Puebloan sites.

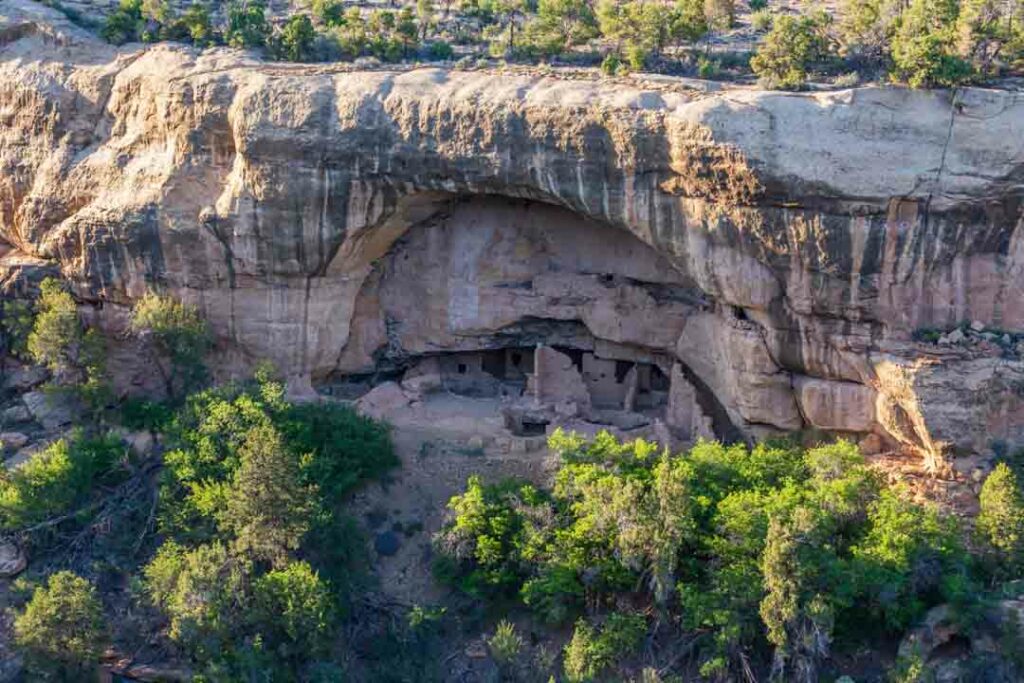

想要感知普韦布洛人当时的生活,还需要穿过当年的小径,前往一处人迹罕至的悬崖建筑——马克杯屋。相比于游客云集的长屋和悬崖宫,这处遗迹无法在地图上搜到,必须在国家公园的管理员陪同下前往。

To experience the life of the Puebloans at that time, you need to pass through the old path and head to a rarely visited cliff dwelling called “Mug House.” Unlike the popular tourist destinations of “Long House” and “Cliff Palace,” this archaeological site cannot be found on maps, and you must be accompanied by a national park ranger to reach it.

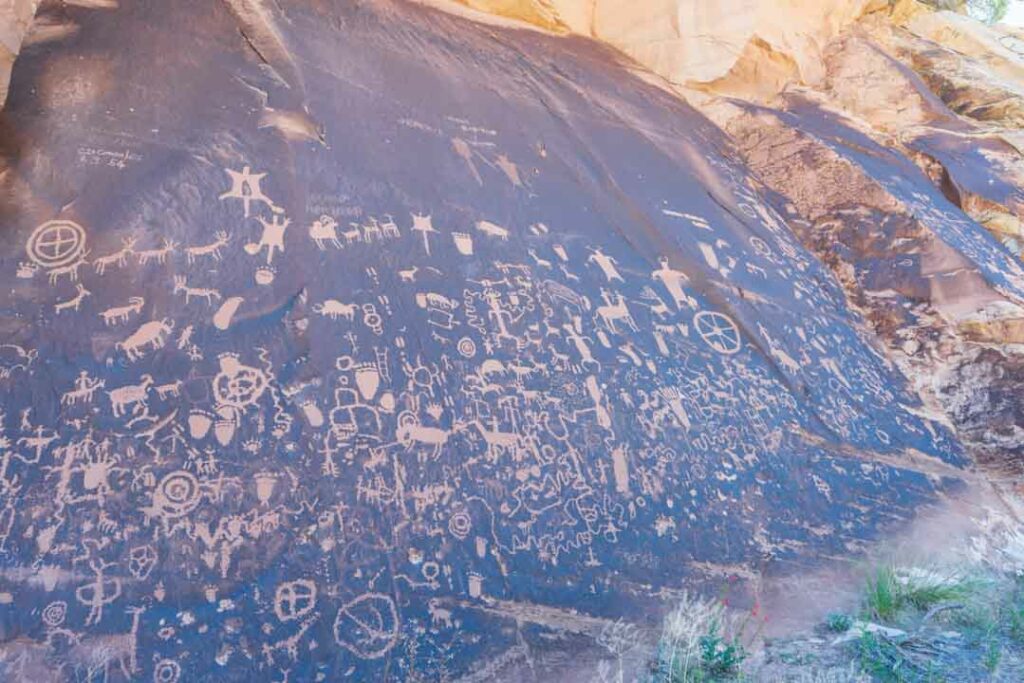

高原五月上午的阳光已经有些毒辣,走下陡峭的山坡,你将会面对一片背阴的岩壁。沿着岩壁边缘修筑好的木板路走,穿过古旧的岩画洞穴,绵延的马克杯屋就将出现在你的面前。

In the harsh May morning sunlight of the plateau, descending the steep hill, you will face a shaded rock wall. Follow the well-built wooden boardwalk along the edge of the rock wall, pass through ancient rock art caves, and the extensive Mug House will come into view before you.

这处遗址因当年发掘出的三个陶制马克杯而得名,遗迹内部至今还散落着不少破碎的陶片。遗址正对着一片稀树峡谷。站在巨大基瓦的前面向远方看去,对面的台地被正午的阳光照得惨白。

This site is named after the three pottery mugs that were excavated there in the past. Even today, many fragmented pieces of pottery can be found scattered inside the ruins. The site faces a sparsely wooded canyon. Standing in front of the massive adobe walls and looking into the distance, the opposite plateau was bathed in the harsh noon sunlight, appearing pale.

峡谷内干热的风摇晃脚下的松柏,经过山壁阴影的冷却,轻轻拂过我的脸庞。这一刻,我仿佛身处八百年前的夏日,感受那份与此地居民一样的荫凉。

The juniper trees and cedars beneath my feet were swayed by the hot and dry wind inside the canyon. After being cooled by the shadows of the cliffs, it gently brushed against my face. At that moment, I felt as if I was transported back eight centuries to a summer day, experiencing the same coolness that the ancient inhabitants of this place once felt.

一千年来,这片峡谷的气候与今天别无二致,桧树、松树、花旗松、橡树和其他在遗址中发现的植物仍然在山丘上生长。高原整体干燥少水的特点使生活在这片土地的人们发展出了独特而节水的旱地农业。他们种植适应干旱的作物,在春天化雪的潮湿土壤上播种。山谷将在七八月份迎来稍多的降雨,这将提供作物生长所需的水分。古普韦布洛人在这一时期还将多余的降水收集起来,以供缺水的旱季使用。在谷物丰收后,他们将种植的豆子和玉米晒干后贮存在房屋的高处,并用黏土密封。他们驯养火鸡和狗,并利用土地提供的一切:松树、仙人掌、蓖麻和向日葵。这种看似粗放的农业实际依赖农民的大量经验,并真真实实地供养了在梅萨维德周围山谷生活着的,比今日数量更多的居民。

For a thousand years, the climate of this canyon has remained unchanged, and the juniper, pine, Douglas fir, oak, and other plants found at the archaeological site continue to thrive on the hills. The overall arid and water-scarce characteristics of the plateau led the people living in this land to develop a unique and water-efficient dryland agriculture. They planted drought-resistant crops and sowed them in the moist soil resulting from the spring snowmelt. The valleys would receive slightly more rainfall in July and August, providing the necessary water for crop growth. During this time, the Ancestral Puebloans also collected excess rainwater to use during the dry season when water was scarce. After a bountiful grain harvest, they dried and stored beans and corn in elevated areas of their houses, sealed with clay. They domesticated turkeys and dogs and made use of everything the land offered: pine trees, cacti, castor beans, and sunflowers. This seemingly extensive agriculture actually relied on the farmers’ wealth of experience and effectively supported a larger population of inhabitants in the surrounding valleys than what exists today.

二、

II.

和当年古普韦布洛人向北迁徙的路径相反,理查德·韦瑟里尔将他的目光投向了未知的南方。在十二世纪中叶的大干旱前,古普韦布洛人文明的中心位于梅萨维德南面约一百英里的查科峡谷。这处峡谷相比于梅萨维德更加偏远。即便是今天,从阿尔伯克基出发,还需要开车近三个小时,并小心翼翼穿过最后四十英里的颠簸的烂泥土路。

In contrast to the Ancestral Puebloans’ northward migration, Richard Wetherill turned his attention towards the unknown south. Before the severe drought of the mid-12th century, the center of the Ancestral Puebloans was in the Chaco Canyon, approximately one hundred miles south of Mesa Verde. This canyon was even more remote compared to Mesa Verde. Even today, departing from Albuquerque, it takes nearly three hours of driving, carefully navigating the rough, muddy roads for the last forty miles.

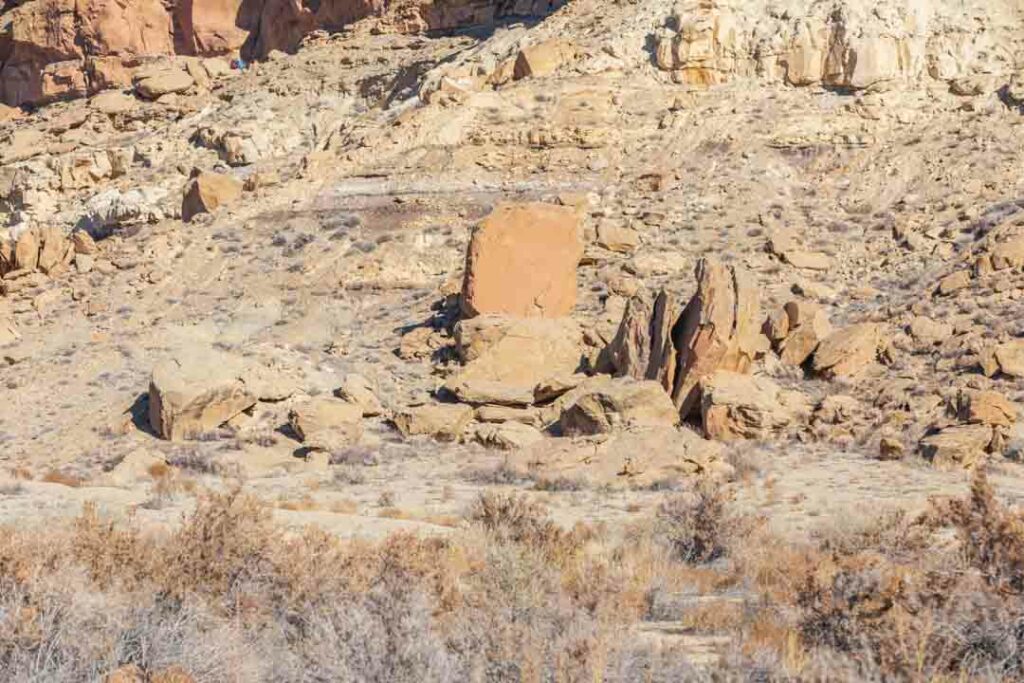

查科峡谷内规模庞大而精细的建筑显然与现在荒凉干旱的环境不相称。在公元一千年前后,这片谷地并不似如今这般荒芜,相对湿润的气候是古普韦布洛人能在这里发展文明的基础。这里的人工建筑背靠悬崖而建,大多都呈现被规划过的 D 字形。峡谷中间是一条已经干涸的旧河道,在查科峡谷最拥挤的时候为此地的居民们提供饮用和耕种水源。

The vast and intricate architecture within Chaco Canyon is clearly incongruous with the current barren and arid environment. Around a thousand years ago, this valley was not as desolate as it appears today, and a relatively humid climate provided the foundation for the development of the Ancestral Puebloans here. The artificial structures were built against the cliffs and mostly followed a planned D-shape layout. In the middle of the canyon, there was a now-dry old riverbed that served as a water source for drinking and cultivation during the peak population of Chaco Canyon.

几个世纪以来的风沙使大部分的人工建筑为沙土和植被所掩盖,时至今日,查科峡谷内两千余个考古遗址只被挖掘出了很少的一部分。

Over the centuries, wind and sand have covered most of the artificial structures with sand and vegetation. As a result, to this day, only a small fraction of the more than two thousand archaeological sites within Chaco Canyon have been excavated.

在这些遗址中,规模最大也最有名的是 Pueblo Bonito(西班牙语意为漂亮的村落)。这座宏伟的建筑主要被用于宗教和政治用途,包括了庆典仪式、行政管理、储存物资、接待访客、天文观测以及埋葬尊贵的死者。这座建筑也是最为标志性的“查科大房子”。查科峡谷的居民们使用了那个时代高超的石工技术,修建了他们的祖先难以想象的巨大房间。这些大房间围绕着一个又一个封闭的基瓦建造。通常情况下,房间的门洞是对齐的,并且使用了一种特殊的砖石结构。

Among these sites, the largest and most famous one is Pueblo Bonito (which means “beautiful village” in Spanish). This magnificent structure was primarily used for religious and political purposes, including ceremonial rituals, administrative management, storage of goods, hosting visitors, astronomical observations, and burial of esteemed individuals. It is also one of the most iconic “Great Houses” of Chaco Canyon. The residents of Chaco Canyon utilized advanced stone masonry techniques of their time to construct incredibly large rooms that their ancestors could hardly have imagined. These large rooms were arranged around one enclosed kiva after another. Typically, the doorways of the rooms were aligned and featured a distinctive brick-and-stone construction.

整个 D 字形的建筑拥有超过 600 个、总占地达三英亩的房间。在部分区域,封闭的房间高达四至五层。除此之外,Pueblo Bonito 的中心有两个巨大的广场。广场中心的大基瓦内环绕着一圈石制座位,并分布有一系列砖石火坑,这与其他的普通基瓦完全不同。整个如同小城市的单体建筑被厚达 3 英尺的巨大砖石墙包围,与外界分割开来。

The entire D-shaped structure comprises over 600 rooms, covering an area of three acres in total. In some areas, the enclosed rooms reach up to four or five stories high. Additionally, at the center of Pueblo Bonito, there are two enormous plazas. The central plaza is surrounded by a circle of stone seats and contains a series of stone-lined hearths, a feature distinct from other ordinary kivas. The entire monolithic building, resembling a small city, is enclosed by massive three-foot-thick stone walls, effectively separating it from the outside world.

建设如此大型的建筑显然不只能靠一代人的努力,查科的所有大型遗址更像是一个长达三百年的首尾接力。建设者为建筑采石,在远处的山上砍伐木材,并在建筑过程中竖起巨大的房块。人们建造了水坝和运河,设计了笔直而纵横交错的大道,将查科峡谷与更加遥远的社区连接起来。这些宽阔的史前道路网络以查科峡谷为中心,向四周辐射并布满了整个新墨西哥州西北角。所有这些项目都需要古普韦布洛人复杂的规划、组织以及区域范围内的合作。从九世纪开始至十一世纪,后代人继承了他们前辈的脚步,一步一步创造了一个独特的、以查科峡谷为中心的文明世界。

The construction of such large-scale buildings clearly could not have been accomplished by just one generation’s efforts. Chaco’s numerous monumental sites appear more like a relay spanning three hundred years. The builders quarried stones, felled timber from distant mountains, and erected massive masonry during the construction process. People constructed dams and canals, designed straight and intersecting roadways, connecting Chaco Canyon with more remote communities. These wide prehistoric road networks centered around Chaco Canyon and radiated outward, covering the entire northwestern New Mexico. All of these projects required complex planning, organization, and cooperation among the Ancestral Puebloans. From the 9th to the 11th centuries, succeeding generations followed in their ancestors’ footsteps, step by step, creating a unique civilization centered around Chaco Canyon.

这个宏大的世界不仅有诸如 Pueblo Bonito 或者 Chetru Ketl 这样的中心建筑。事实上,支持这些雄伟奇观的,是无数这一带星罗棋布的小村庄。尽管建于同一时代,这些村庄的建筑与峡谷内的建筑相比极为简陋,大多建筑甚至被岁月侵蚀得只剩地基。有些村庄有着自己独立的神龛或祭祀中心。位于查科峡谷稍偏远地带的 Casa Rinconadas 便是其中有代表性的一个。它是一个孤立的大基瓦,并具有大基瓦的所有典型元素:砖石火坑、砖石拱顶以及环绕基瓦的壁龛和砖石座位。这个大基瓦甚至有一条从山脊中挖出的长地下通道,被用于制造祭祀仪式中的意外“惊喜”。

This grand civilization not only comprised central structures like Pueblo Bonito or Chetro Ketl but was also supported by countless small villages scattered throughout the region. Although these villages were contemporaneous with the structures in the canyon, their buildings were much simpler in comparison, and many have been eroded by time, leaving only their foundations. Some villages had their independent shrines or ceremonial centers. Casa Rinconada, located in a slightly remote area of Chaco Canyon, is a representative example. It is an isolated great kiva and exhibits all the typical features of such structures: masonry hearth, masonry benches, niches, and walls surrounding the kiva. This great kiva even has a long underground passageway dug into the ridge, used for unexpected “surprises” during ceremonial rituals.

体会查科峡谷中这些宏大中心建筑最好的方式,是沿着岩壁的一条古老的小道,爬上 Pueblo Bonito 背后的悬崖。古普韦布洛人在悬崖之上也建造了一个规模稍小的祭祀建筑,似乎是要宣誓自己与天的连结。沿着悬崖边缘的小路走,你可以从不同的角度俯瞰 Pueblo Bonito 和 Chetro Ketl 这两处峡谷的中央核心。巨大的建筑群如同一张大饼一样摊开在你的面前,建筑物的几何形状和大房间之间的相互关系都展现得一清二楚。这种感觉与在残垣断壁之间的感受完全不同,只有在这一刻,你才会真正明白古普韦布洛人惊人的巧思。

The best way to appreciate these grand central buildings in Chaco Canyon is by following an ancient path along the cliffside and climbing up the cliffs behind Pueblo Bonito. The Ancestral Puebloans also constructed a slightly smaller ceremonial structure on top of the cliffs, seemingly to affirm their connection with the heavens. Walking along the edge of the cliffs, you can overlook Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl, the two central cores of the canyon, from different angles. The vast buildings spread out before you like a large pancake, revealing the geometric shapes of the structures and the interconnections between the large rooms. This feeling is completely different from exploring among the ruins; only at this moment do you truly understand the astonishing ingenuity of the Ancestral Puebloans.

然而再辉煌的文明,终究有她衰败的一天。公元十二世纪,查科峡谷迎来了一次长达五十年的大旱。同一时期,峡谷内的新建筑的砌筑风格和石头本身也变得与早期建筑截然不同,反而更像是北方梅萨维德的风格。或许是来自北方的入侵,或许仅仅是因为生态环境和农业的崩溃,世代居住于此的古普韦布洛人逐步离开了这里。

However magnificent a civilization may be, it will eventually experience its decline. In the 12th century AD, Chaco Canyon faced a prolonged drought that lasted for fifty years. During the same period, the construction style of new buildings within the canyon and the stones themselves became drastically different from the earlier architecture, resembling more the style found in the northern region (Mesa Verde). It could have been due to invasions from the north or simply the collapse of the ecological environment and agriculture, but the Ancestral Puebloans who had inhabited the area for generations gradually abandoned it.

Pueblo Bonito 中延续三百多年的精英墓地在约 1130 年终结。随着社会的全面崩溃,外围村落和社区的人口锐减,查科峡谷内的建筑群被迅速废弃。如同前一节说的那样,一大部分居民迁往了北方。

The elite funeral practices that persisted in Pueblo Bonito for over three hundred years came to an end around 1130 AD. As the society experienced a complete collapse, the population in the surrounding villages and communities sharply declined, leading to the rapid abandonment of the architectural complexes within Chaco Canyon. As mentioned earlier, a significant portion of the population migrated northward.

三、

III.

与其说这些居民迁往了北方,不如说他们回到了北方。

Rather than saying the Ancestral Puebloans migrated to the north, it is more accurate to say they returned to the north.

在早于查科峡谷兴盛的年代,梅萨维德就是古普韦布洛人的一个文化中心。古普韦布洛人早在公元六世纪就已经在梅萨维德定居。这片区域除了肥沃的土壤和临近的水源,同时存在丰富的猎物可供狩猎。这使得他们从半游牧生活逐步过渡到定居的农业生产。

In the era preceding the prosperity of Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde was a cultural center for the Ancestral Puebloans. They had settled in Mesa Verde as early as the 6th century AD. The region offered fertile soil, proximity to water sources, and abundant wildlife for hunting, which facilitated the transition from a semi-nomadic lifestyle to settled agriculture.

“耕作意味着一次在一个地方待上几个月甚至几年。这使他们能够了解土壤,并了解可以种植和培育到成熟和收获的各种植物。”

“To farm meant being in one location for months and years at a time. It allowed them to get to know the soil, and to learn the kinds of plants that could be grown and nurtured through maturity and through harvest.”

随着耕种的作物如玉米、豆类和南瓜在他们的饮食中变得越来越重要,这些早期的农民开始建造被称为石屋的永久性住宅。在学习烹饪和储存时,他们不得不抛弃了曾被广泛使用的木制提篮,转而制作各式各样的陶器。

As corn, beans, and squash grew increasingly essential in their diet, these early farmers embarked on constructing permanent dwellings called pithouses. Mastering cooking and storage techniques prompted them to forsake the once widely used wooden baskets in favor of crafting diverse pottery vessels.

在随后的三个世纪,梅萨维德区域出现了更大型的村落。古普韦布洛人从小而孤立的半地下石屋中离开,并在地面上修建更大型的、由木杆和土坯制成的住房。原本地下的石屋则演变成了深度更深的坑道。这些新出现的坑道结构不再主要用于家庭活动,而是被整个村落共享,作为聚会场所和举行仪式的地方。纺织、珠宝和工具制造等手工艺得到了长足的发展,陶器也从单调的灰色转变为了黑白相间的花纹。随着农业的繁盛,这一带的人口密度急剧增加,并在公元九世纪达到了顶峰。

Over the following three centuries, the Mesa Verde region witnessed the emergence of larger villages. The Ancestral Puebloans departed from the small and isolated semi-subterranean pithouses and began constructing larger houses above ground, made from wooden poles and adobe. The original underground pithouses evolved into deeper pit structures. These newly established pit structures were no longer primarily used for individual households but were shared by the entire village, serving as gathering places and ceremonial sites. Craftsmanship, including textile production, jewelry making, and tool crafting, flourished, and pottery evolved from simple gray to intricate black-and-white designs. With the prosperity of agriculture, the population density in the area sharply increased, reaching its peak in the 9th century.

可是文明发展到一定程度以后,都只将会有一个中心。随着查科峡谷在九世纪越来越大的影响力,以及梅萨维德本地越发不可预测的干旱,世居于此的古普韦布洛人开始大量南迁。由于人口的持续迁出,很多的建筑仅仅过了数十年就被完全废弃。新的房屋也因缺乏技术与劳力变得更加粗制滥造。

As civilizations develop to a certain extent, they tend to gravitate towards a single center of influence. With Chaco Canyon gaining increasing prominence in the 9th century and the Mesa Verde region experiencing unpredictable droughts, the Ancestral Puebloans who had long inhabited the area started migrating southward in large numbers. As a result of this continuous outmigration, many buildings were abandoned after only a few decades. The construction of new houses also suffered, becoming more rudimentary due to a lack of technology and labor.

这一时期的建筑风格也被查科峡谷所影响,建于公元 1000 年左右的远景屋(Far View House)完全采用了查科风格的大房子式建筑。自始至终,远景地区都是梅萨维德人口最稠密的地方,这也清楚地表明了先进的查科式生活方式对梅萨维德的广泛渗透。

During this period, the architectural style was influenced by Chaco Canyon, as evidenced by structures like the Far View House, which was built around 1000 AD and fully adopted the Chacoan-style great-house architecture. Throughout this period, the Far View region remained the most densely populated area in Mesa Verde, clearly indicating the widespread influence of the advanced Chacoan way of life in Mesa Verde.

所以当查科峡谷在十二世纪经历沉重的打击后,迁回此地的古普韦布洛人面对着一个熟悉又陌生的“故乡”。

So, when the Chaco Canyon suffered a heavy blow in the twelfth century, the Ancestral Puebloans, who later returned to this place, faced a familiar yet unfamiliar “homeland”.

这造就了梅萨维德常见的,同一区域在不同历史时段反复重建的遗迹。他们的先辈为了更好的生活离开了这里。后辈们也一样为了追求更好的生活讶然回归。这些后代的建设者根据他们的需要和当前流行的风格,对前人遗留的建筑和村庄进行改造与扩建。

This has resulted in the common occurrence of the Mesa Verde, with remnants of the same area being repeatedly rebuilt in different historical periods. Their ancestors left this place in search of a better life, and their descendants, similarly driven by the pursuit of a better life, returned unexpectedly. These later generations of builders, based on their needs and the prevailing architectural styles of their time, modified and expanded upon the structures and villages left behind by their predecessors.

韦瑟里尔台地展出了一处这种类型的村庄广场。广场的一边是一座可以追溯到公元 1258 年的塔楼,另一边则是一个建于大约 200 年前的基瓦。从两者的墙壁就能轻易看出其年代的区别。

The Wetherill Mesa features a village plaza showcasing this type of village development. On one side of the plaza stands a tower that dates back to around 1258 AD, while on the other side is a kiva built approximately 200 years ago. The walls of these structures clearly display the differences in their ages:

对于塔楼而言,房屋的墙壁由精心打制的岩石建成,并小心地排成整齐的行列。新砌的墙壁里外各有一层石砖,中间填满了泥土和粗糙的石头。这些粗糙的石头很可能来自更早期的建筑,例如那个较早的基瓦。它的墙壁只有单独一层被粗略修整的石头,墙体也更加凹凸不平。

The tower’s walls are constructed from carefully crafted rocks, precisely aligned in neat rows. The newly rebuilt walls have an outer and inner layer of stone bricks filled with mud and rough stones. These rough stones likely originated from earlier constructions, such as the older kiva. The kiva’s walls, on the other hand, have only one layer of roughly trimmed stones, making the walls more uneven and irregular in appearance.

同样的建筑还存在于远景地区和查平台地。当人们回到这里,总会使用一些旧的石头和新的木材修葺被他们祖先抛弃的房间。这样建造的房屋从另一方面来说,也增添了梅萨维德建筑的随意性。完全不同于查科式建筑的提前计划,这里的建筑似乎完全没有一种统一的规范。这一点也可以从梅萨维德建筑的容积率看出。或许因为资源受限,再次兴盛的梅萨维德总是以任何可能的方式最大化利用空间,没有任何区域被认为是建筑的禁区。

Similar constructions can also be found in the Far View area and the Chapin Mesa. When people returned to these places, they tended to use some old stones and new wood to repair the rooms that were abandoned by their ancestors. This kind of construction adds a sense of randomness to the Mesa Verde architecture. Unlike the pre-planned Chacoan architecture, the buildings here seem to lack a unified set of standards. This can also be seen in the volume of Mesa Verde buildings. Perhaps due to limited resources, the resurgence of Mesa Verde always maximizes the use of space in any possible way, with no area considered off-limits for construction.

梅萨维德的这场“文艺复兴”并没有能持续太久。尽管从建筑技巧和艺术上,这里已经成功超越了查科峡谷,但最终这里衰落得甚至比查科峡谷更加彻底。在十三世纪,梅萨维德的居民在悬崖宫对面的山顶规划并建造了一座庞大的太阳神庙。这座神庙有着类似查科峡谷的 D 字形轮廓,却既没有屋顶,也少有文物出土。或许这座神庙只被用于天文观测,但更大的可能则是这座建筑从未完工。

The “Renaissance” of Mesa Verde did not last long. Despite surpassing Chaco Canyon in architectural techniques and artistry, Mesa Verde eventually declined even more thoroughly than Chaco. In the thirteenth century, the residents of Mesa Verde planned and built a massive Sun Temple on the mountaintop opposite the Cliff Palace. This temple had a D-shaped outline similar to Chaco Canyon but lacked a roof and yielded few artifacts. Perhaps this temple was used for astronomical observations, but it is more likely that the construction was never completed.

国家公园的一处解说牌写道:“公元 1225 年,出生在这些悬崖上的孩子们将在他们的一生经历许多变化。在大约 75 年的时间里,他们和他们的家人从山顶迁往悬崖屋中,经历过最拥挤的人口高峰,最后是整个区域的人口总崩溃。”

The caption on a national park interpretive sign reads: “Children born in one of these cliff dwellings in 1225 CE experienced many changes in their lifetime. Over the course of roughly 75 years, they and their families witnessed the migration from mesa top villages into alcove communities; a significant peak in the area’s population; and then the final exodus from the entire region.”

这场可怕的人口崩溃不仅仅发生在梅萨维德,包括查科峡谷、尚都高原(Shonto Plateau)在内的整个四州交界地区全都出现了人口锐减。古普韦布洛人再次迁往更远的南方。没有人具体知道这次崩溃的原因。考古学家在这里发现了周期性战争的痕迹。人口膨胀和部族冲突使得梅萨维德的植被消失,台地顶部的最后一棵树于 1281 年被砍倒。随之而来的,则是一场长达二十年的大旱。

This terrifying population collapse didn’t only occur in Mesa Verde, but also affected the entire Four Corner region, including the Chaco Canyon and the Shonto Plateau. The Ancestral Puebloans once again migrated to the south, but further away. Nobody knows the exact cause of this collapse. Archaeologists have found evidence of cyclical warfare here. The population expansion and tribal conflicts led to the disappearance of vegetation in Mesa Verde. The last tree on the mesa was cut down in the year 1281, following a prolonged drought lasting for twenty years.

我们能够确定的是,到了十三世纪的最后一年,梅萨维德又变得悄无人烟。这里绵延八百年的农业文明就此终结。相比于八百年前,梅萨维德多了无数壮观却空空如也的建筑,以及一片秃顶的荒山。

By the end of the 13th century, Mesa Verde had become deserted once again. The agricultural civilization that had thrived for eight centuries came to an end. In contrast to eight centuries ago, Mesa Verde now had numerous spectacular yet empty buildings, as well as a barren mountain with a bald top.

尾声、

IV.

在悬崖上居住了大约 150 年后,古普韦布洛人再一次迁徙。他们中的一部分在普埃尔科河(Puerco River)边安顿下来,玉米、豆子和南瓜田布满了河边的洪泛区。他们在岩石上刻下太阳的方位,用以标记夏至和冬至的日期。只是这座村庄也没有逃离被遗弃的命运,一百多年后,定居于此的古普韦布洛人再次离开。

After living on the cliffs for about 150 years, the Ancestral Puebloans migrated once again. Some of them settled along the Puerco River, where fields of corn, beans, and pumpkins adorned the floodplain. They carved the position of the sun on rocks to mark the dates of the summer and winter solstices. However, this village did not escape the fate of abandonment either. Over a hundred years later, the settled Ancestral Puebloans left once again.

当然也有一些普韦布洛村落保留到了今天,其中最有名的莫过于陶斯村。陶斯的居民在一度抛弃村庄后又回到了那里。今天,这个有着千年历史的村落与梅萨维德和查科峡谷并列为了普韦布洛人的三大世界文化遗产。陶斯那别具一格、充满设计感的建筑也为当代艺术家提供了无数创意。

Some Puebloan villages have survived to this day, and the most famous among them is Taos Pueblo. The residents of Taos returned there after abandoning the village for a time. Today, this village with its millennia-long history stands alongside Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon as one of the three major world cultural heritage sites of the Puebloans. The distinctive and creatively designed architecture of Taos also provides countless inspirations for contemporary artists.

或许现代普韦布洛人从未忘记他们祖先所呆过的地方。他们通过每一代人的口头传承了解他们祖先的故事。他们的后代会回到祖先的遗址祈祷,留下祭品,试图与死去的祖先交流。现代普韦布洛人将这些史前遗址视为 “祖先的脚印”,将不断的迁徙视为“民族的记忆”。

Perhaps modern Puebloans have never forgotten the places where their ancestors lived. They orally pass down the stories of their ancestors after generations. Their descendants return to the ancestral sites to pray, leave offerings, and attempt to communicate with their deceased ancestors. Modern Puebloans regard these prehistoric sites as “footprints of their ancestors” and view the ongoing migrations as “the memory of their nation.”

而理查德·韦瑟里尔,这个永远改变了普韦布洛考古的人,则将他的余生都留给了查科峡谷。因为他不专业的发掘被考古学家阻止,他转而在查科峡谷经营牧场和贸易站。1910 年 6 月 10 日,他卷入了一场与当地人的争执,最后不幸被一名纳瓦霍青年枪杀。他的尸骨被埋在了 Pueblo Bonito 西面的一处墓地。后来,他的家人也永远长眠在了那里。

And Richard Wetherill, the man who forever changed Pueblo archaeology, devoted his remaining years to Chaco Canyon. As his amateur excavations were discouraged by professional archaeologists, he turned to ranching and operating a trading post in Chaco Canyon. On June 10, 1910, he became involved in a dispute with the locals and tragically lost his life when he was shot by a Navajo youth. His remains were buried in a cemetery to the west of Pueblo Bonito. Later, his family also found their eternal rest there.